For 2020, it had been planned to put the Salzburg Festival itself under the microscope, and also the myth it has been creating by constantly retelling, for example, the works of Strauss and Mozart, or the Jedermann/Everyman play.

Oedipus, Medea and the heroes of the Trojan War; war, flight, fate, self-finding and loss of self; sacrifice, guilt and atonement are at the core of these works, the ancient myths which the 2019 Festival summer aspired to explore anew: Mozart’s Idomeneo, Cherubini's Médée, Offenbach's Orphée aux enfers …

The Lithuanian soprano Asmik Grigorian had already débuted at the Salzburg Festival as Marie (Wozzeck) in 2017 and captivated the public with her authentic interpretation.

‘Spiel der Mächtigen’ (‘Game of the Mighty’) was the motto of the 2009 Salzburg Festival programme, which was also overshadowed by a leadership debate. Handel, Rossini, Beethoven, Mozart and Haydn were the main features of the opera season – and Luigi Nono, whose superlative work Al gran sole carico d’amore was shown in the Felsenreitschule/Summer Riding School.

Also in his second season Markus Hinterhäuser arranged for a scenic production as part of the ‘Continents’ series: Salvatore Sciarrino’s opera Luci mie traditrici directed and designed by the German artist Rebecca Horn in the Kollegienkirche – used once more for Festival productions – and lit by Beat Furrer with great musical sensitivity.

Jürgen Flimm started his term as Artistic Director with rarities such as Joseph Haydn’s Armida directed by Christof Loy and Hector Berlioz’s opera about an artist, Benvenuto Cellini. Therefor, film director Philipp Stölzl exploited the Cinemascope stage of the Large Festival Hall to make the grand opéra ‘approach the feeling of great cinema’1 and interpreted it as an opulent stage show, while Valery Gergiev unleashed ‘a storm of sound’2.

After the turbulence erupting from the drama team – Peter Stein’s successor Ivan Nagel was engaged for only one season – Frank Baumbauer took over the department as artistic consultant and brought out the German-language première of the Shakespeare adaptation Schlachten by Tom Lanoye and Luk Perceval on the Perner-Insel.

In 1992, Saint François d’Assise by Olivier Messiaen celebrated its first performance under Esa-Pekka Salonen as conductor and Peter Sellars as director. Although the production aroused controversy at the time, it went down in the history of critical reception as one of the most important productions and to the present day has always stood for the Festival’s programmatic new start.

Despite Peter Stein’s successes and his benchmark works, not least in Alban Berg’s Wozzeck in the Easter Festival production with Claudio Abbado, Gerard Mortier found it was time for a more innovative theatre. The head of drama Peter Stein took his farewell with Grillparzer’s Libussa in 1997.

After Herbert von Karajan’s resignation from the Board of Directors, a selection committee was set up to deal with his succession. Even before this was settled, Herbert von Karajan died on 16 July 1989 at the age of 81 in his house in Anif.

The competing of the ‘Scene’ continued to cause further tumult in the Festival District. Besides local stars and international ensembles, Festival artists like Friedrich Gulda, Gidon Kremer and Rolf Hochhuth used the alternative forum more and more to present new contexts for their art.

A row about the freedom of artistic expression rocked the Festival in 1987: George Tabori’s production of Franz Schmidt’s Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln was prohibited after the first night. To the clergy, the drastic world of images conceived by the director seemed incompatible with the consecrated church building.

Herbert von Karajan set a further accent in the Verdi repertoire: for the first time, in 1979, Verdi’s Aida was on the programme of the Salzburg Festival.

The new production of Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte in the Felsenreitschule/Summer Riding School, headed by James Levine and Jean-Pierre Ponnelle, turned out to be a sensation.

One of Herbert von Karajan’s great aspirations was to promote young talents. Artists like Anne-Sophie Mutter, Agnes Baltsa, Mariss Jansons, Seiji Ozawa and Riccardo Muti owed much to him for the great boost he gave their careers.

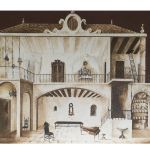

The successful production from the previous year, Cavalieri’s Rappresentatione di anima e di corpo – with the Mozarteum Orchestra – relocated in 1969 to the Kollegienkirche, where it remained in the repertoire until 1973. It was the first time since 1922 that the Kollegienkirche was used again as a venue for the Salzburg Festival.

During the climax of the student and civil rights movement, Salzburg celebrated the revival of the Baroque Theatre of the World with Emilio de’ Cavalieri’s Rappresentatione di anima e di corpo, likewise the Italian opera buffa.

Straight drama still had a hard time to vie with the dominance of the opera, which had a huge Cinemascope stage at its disposal in the Large Festival Hall. But the latter wasn’t suitable for straight drama productions.

After 1945, Ernst Lothar and Oscar Fritz Schuh dominated the drama department.

After the regular TV programme started operating in Austria on six days a week starting at 8 pm as of January 1957, ORF decided in June 1958 for the first time to broadcast Festival events on television as well.

The Festival’s Board of Directors had already resolved as early as December 1954 to fill the gap left by Furtwängler’s death and engage Herbert von Karajan. However, he cancelled his engagement in 1955.

In the late 1940s, the process of normalization in the city and the countryside was becoming clearly perceptible, also in the Salzburg Festival. In February for instance, the temporary power cuts ceased and for the first time nearly all stage scenery could be made in the Festival workshops in Salzburg, saving costly and complex transportation.

Film footage (151 feet in fact) documents ‘Austria’s greatest artistic event’ in 1948 in word and image: Helene Thimig rehearsing Jedermann/Everyman, Paula Wessely and Horst Caspar in Grillparzer’s Des Meeres und der Liebe Wellen/The Waves of Sea and Love, also the summit meeting of the two maestri and artistic rivals: Wilhelm Furtwängler, who conducted a new Fidelio at the Festival Hall, and Herbert von Karajan in his opera début.

The 1947 Salzburg Festival opened with Jedermann, with stage direction by Reinhardt’s widow Helene Thimig. Jedermann was played by Attila Hörbiger. Thimig’s production after Max Reinhardt remained in the repertoire until 1951.

The extended Festival Hall by Clemens Holzmeister had already aroused Goebbel’s displeasure in 1938.

In February and March 1938, things happened thick and fast. Just a few days after the meeting between Federal Chancellor Schuschnigg and Adolf Hitler and the signing of the Berchtesgaden Agreement, which assured the Nazis far-reaching political influence in Austria, Arturo Toscanini cancelled his appearances at the Salzburg Festival.

Arturo Toscanini already called for the building of a new festival theatre in 1936, while those in charge of the Salzburg Festival supported another reconstruction of the existing Festival Hall by Clemens Holzmeister.

Besides the works of Mozart, from the mid-1920s on Richard Strauss’s operas formed a second mainstay of the Salzburg Festival. In 1926, Ariadne auf Naxos was in the repertoire, in 1929 the first Rosenkavalier, which came to be a central work in the Festival programme.

When a music programme was planned for the first time for the newly established Festival in 1922, it was obvious that this should be held with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and the ensemble of the Vienna State Opera.

In 1927, improvements were yet again carried out on the Festival Hall, this time the stage area. A proscenium curtain was added, the stage technics refined, the orchestra pit enlarged. The intention was to perform opera in this theatre.