Pastries, Myths and World History

Highly diverse baroque operas by Rameau, Handel and Vivaldi offer a kaleidoscope of the human and all-too-human condition with their tales of love and power.

In German, the problems begin as soon as you try to define the gendered article of the noun “baroque”, on which opinions differ between the masculine and neutral. There is something to be said for Bruno Preisendörfer’s winking characterization of the epoch as “postmodernism of the renaissance”. Unlike these self-descriptions, however, thus the literary scholar, the term baroque hails from “an element of cultural slander”, viewing the era from the rigid perspective of the 19th century, which was itself in thrall to classicism. “Barocco” presumably goes back to a term used by 16th-century Portuguese jewellers to describe an irregularly shaped, perhaps even unbeautiful pearl.

Yes, perhaps unbeautiful: when the 2025 Salzburg Festival presents three great stage works by three fundamentally different composers of the baroque era – Jean-Philippe Rameau, George Frideric Handel and Antonio Vivaldi – each of these sumptuous masterworks casts a spotlight on an era of extremes, differences, and seemingly insurmountable contradictions, each in its own manner. Therein, they cannot but reflect the problems, the divisions and wounds of the present.

Vivaldi, the red priest. What’s the old Hollywood rule of thumb? Start with an earthquake – then slowly escalate. Well then: an earthquake shook Venice on 4 March 1678, the day Antonio Vivaldi was born, the son of a musician and a tailor’s daughter. Was that frightening natural event the “mortal danger” which caused the midwife to perform an emergency baptism? Or did the newborn already show symptoms of that “strettezza di petto”, that “constriction of the chest” which was to plague Vivaldi’s health throughout his life, and is today mostly thought to signify a case of asthma? What is certain is that Vivaldi has been beloved throughout the world for his Quattro Stagioni ever since he was rediscovered in the 20th century – those violin concertos he composed as resonating characterizations of the four seasons. As for his father, the violin was the short-winded young man’s main instrument. He was, however, designated for a church career and consecrated a priest in 1703.

Soon, however, contradictory anecdotes about Vivaldi were in circulation. Known as “il prete rosso” (“the red priest”) for the colour of his hair, he worked as a music teacher at the Ospedale della Pietà, a girls’ orphanage, causing a stir with its orchestra of highly talented girls. Supposedly, the pious man only laid down his rosary when he took up the quill to write an opera. And yet, he was said to have interrupted a mass once to quickly scribble down a fugue theme in the sacristy. Vivaldi himself once declared that he was able to fulfil his priestly duties “hardly longer than one year”, for “due to my illness I had had to interrupt the celebration of mass three times, stepping away from the altar”. A slight exaggeration, in order to follow his true passion?

Even while still fulfilling his comprehensive duties at the Ospedale, Vivaldi was drawn to the stage. While the political, military and economic power of La Serenissima had faded to a fraction of its former importance by Vivaldi’s lifetime, its cultural strength was still formidable: in Venice, the newly-minted genre of the opera had been transformed from a purely courtly and private artistic diversion into a publicly accessible pleasure as early as the 1630s.

During the second half of the century, up to nine large and eleven smaller opera houses vied for the patronage of paying audiences of every social background.

According to his own record, Vivaldi composed no less than 94 operas. Today’s research concludes that the music of not even a third of these has come down to us, wholly or in part. The fact that so many stage works of the baroque era have been lost is due mainly to theatrical practice at the time: unlike instrumental music, which publishers found repaid their efforts, every opera performance had to be tailored to the ensemble at hand. This was easier and more economically accomplished with scores and parts that were hand-written, cut-out, pasted-over, cobbled-together – and then often quickly forgotten.

Thus, arias were transposed, rewritten, newly composed, cut or exchanged, all according to the wishes and virtuoso specialties of the vocal superstars who were absolutely central to the genre. The conventions of baroque opera allowed one number to be replaced by another, as long as it expressed the same emotion, the same affect of the character in question at this juncture in the action. This led to the so-called “pasticcio”, whose ingredients were as mixed as the plethora of Italian pastries: works cobbled together from the music of numerous composers – as an attraction, due to time pressure or the demand for current “hits” from singers and audiences alike.

A modern pasticcio. In the spirit of this historical practice, the director Barrie Kosky developed a modern concept of a Vivaldi pasticcio together with the dramaturge Olaf A. Schmitt for the Salzburg Whitsun Festival: Hotel Metamorphosis has an exquisite ensemble undergo various mythical transformations in various roles, as the Roman poet Ovid described them in his Metamorphoses. The combination of arias and instrumental movements by Vivaldi and Ovid’s texts is “like knitting”, according to the director, “weaving two threads together that, although they are different, echo and reflect each other very beautifully.”

In its course, Cecilia Bartoli, Nadezhda Karyazina, Lea Desandre, Philippe Jaroussky and the star actress Angela Winkler turn into Orpheus and Eurydice, Echo and Narcissus, Pygmalion and his statue. Kosky, whose acclaimed previous productions at the Salzburg Festival were Offenbach’s Orphée aux enfers and Janáček’s Kat’a Kabanová, promises “an elegiac meditation on themes of Ovid with music of Vivaldi”.

Handel’s birth. When was George Frideric Handel born? In 1685, the same year as Johann Sebastian Bach, as older readers may have learned in school. On Handel’s famous tomb at Westminster Abbey, however, where the French sculptor Lous-François Boubiliac showed the composer in the modern manner, as a private person, without a wig and holding a page of The Messiah, the engraving states: “born February XXIII. MDCLXXXIV” – on 23 February 1684. A mistake in such a prominent place? No. In solving this mystery, Handel’s subsequent titular opera hero comes into play. After all, the beginnings of years in the old Roman, “Julian” calendar introduced by Julius Caesar in 45 BC, which parts of the Western world used well into modern times, were defined historically and varied by region. In Great Britain, it was 25 March, the feast of the Annunciation – and remained that way until 1752, when Pope Gregory XIII implemented his calendar reform. Therefore, Handel’s birthday landed in the “old” year 1684.

If Venice was a capital of music, London was something akin to a world capital: as they formerly did on the Adriatic, now the threads of international commerce of an entire empire converged on the banks of the Thames. The same was true of people. London’s population was estimated at half a million in 1712, the year Handel moved there; at the end of his life, its population is said to have reached 650,000: the prototype of the ravenous metropolis.

Born in Halle on the river Saale in what was then the Duchy of Magdeburg, soon known in Hamburg as a young opera composer, celebrated during professional sojourns in Florence, Rome, Naples and Venice as “il caro sassone”, the “dear Saxon”, Handel became court kapellmeister to the Elector Georg Ludwig of Hanover, who was later to ascend to the English throne as George I. In London, he was an independent entrepreneur, blessed with a changeful, yet overall glittering career: no wonder that in retrospect, Handel is considered a “European” composer par excellence.

The best from all over the world was just good enough for London in those days. While musical theatre developed in a separate direction in France – also because that country maintained its scepticism towards the castrati so celebrated in Italy – England was fascinated by these attractive musical “imported goods”. In 1708, Nicolini became the first castrato to cause an enormous stir and lasting enthusiasm in London. Originally, opera still meant linguistic confusion, as the stars from abroad sang nothing but Italian, while homegrown luminaries stuck with English. “At length,” the satirical magazine The Spectator wrote in 1711, “the Audience grew tir’d of understanding Half the Opera, and therefore to ease themselves Entirely of the Fatigue of Thinking, have so order’d it at Present that the whole Opera is performed in an unknown Tongue.”

Magnificent operatic pomp. In 1724, Handel landed one of this long-running hits with Giulio Cesare in Egitto: in its first season alone, this musically magnificent, varied yet psychologically sophisticated opera was performed 13 times. Revivals during later seasons brought this number to 38, topped only by the 53 performances of his Rinaldo. Starting in 1922, this piece was also to launch Handel’s rediscovery as a musical dramatist in modern times. The audience at that first performance valued not only its musical and theatrical quality, but also several additional attractions: first of all, Caesar and Cleopatra were familiar figures to the educated classes, so the intricacies of the plot were easier to follow. Furthermore, the public had become accustomed to newspapers and publishers flourishing without censorship: this meant long, enlightened and satirical novels such as those by Daniel Defoe, Jonathan Swift and Henry Fielding, but also the precursors of today’s “yellow press”.

Bridgerton, the current series of novels and streamed dramatizations, projects this enthusiasm back into a past that may be fictitious, but is historically correct at its core: gossip mesmerizes the masses, who love catching a glimpse into the bedrooms of the rich and powerful, be it true or invented, on the opera stage or in reality. And doesn’t the strong ruler Caesar, arriving as an outsider, also reflect the Hanoverian George upon the English throne?

Dismissed. On the outside, baroque opera obeyed similar laws later governing classic Hollywood: stars and flashy displays impressed the audience, and bitter rivalries between different opera companies were the norm. And yet the rollercoaster fate of Handel’s enterprises depended heavily on his getting on with the mezzo-soprano castrato who created the role of Giulio Cesare: Francesco Bernardi, known as Senesino. After years of successful collaboration, their equally hot temperaments finally proved incompatible. When Handel abruptly dismissed the obstreperous star in 1733, many of his other singers left in solidarity with Senesino, so that the composer and impresario ultimately lost not only his ensemble, but also the public’s esteem …

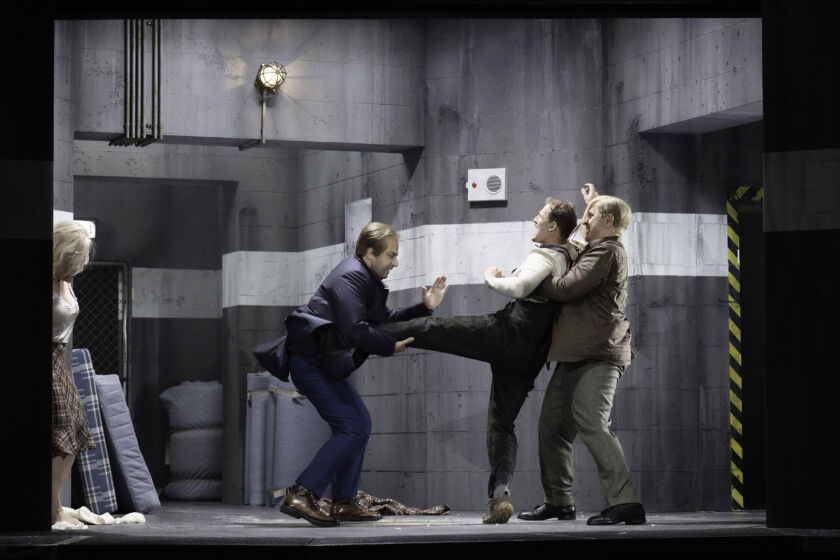

That is one factor Salzburg’s illustrious cast can surely count upon: Christophe Dumaux (Cesare) falls in love with Olga Kulchynska, who plays her cards cleverly as Cleopatra – and finally manages to rid herself of her scheming brother Tolomeo, sung by Yuriy Mynenko. Lucile Richardot embodies the suffering widow Cornelia, Federico Fiorino her son Sesto, who is plotting his revenge. Emmanuelle Haïm conducts the Salzburg Bach Choir and Le Concert d’Astrée. The director Dmitri Tcherniakov is sure to deliver a staging that reveals how everyone soon ends up with blood on their hands in this amorous and political game.

Aging revolutionary. Which leaves the third and oldest in this Festival troika of baroque composers: Jean-Philippe Rameau. At the age of 18, he spent a while in Italy, working for a theatre director in Milan – but at 19, he was already back in his French homeland, never to leave again: born in Dijon in 1683 and died in Paris in 1764, Rameau was in some ways the opposite of Handel the internationalist and also of Vivaldi, who travelled extensively. As a musical dramatist, he was a late bloomer: he only began writing for the opera stage at the age of 50. The fact that Rameau brought the harmonic ideas of his ground-breaking works of musical theory, still important today, as well as the rich musical detailing of his character pieces for harpsichord to the stage was considered almost scandalous at the time. Jean-Baptiste Lully might have been dead for half a century, but he had created a specifically French version of baroque opera: five acts, with a prologue glorifying the king; featuring chorus and lots of ballet; omitting virtuoso castrati and da-capo arias, but including vocal and instrumental numbers that transitioned and blended as seamlessly as possible. Lully’s models were considered sacrosanct by his conservative followers. Rameau’s imaginative, more liberated aesthetic – for example his more expressive management of the vocal lines, and not least his brilliant construction of dramatic orchestral movements illustrating the action on stage – won over the more modern-minded parts of his audience, resulting in vehement clashes between the “Lullists” and the “Ramists”.

Directly to the heart. “His music goes directly to our hearts, like a sunbeam cutting through the black infinity of the cosmos until it finally meets the human eye, a green leaf, a rose in bloom”: the person praising Rameau in such flowery words is Teodor Currentzis. Together with his Utopia chorus and orchestra, he brings Rameau’s “tragédie en musique” Castor et Pollux (1737) to life in two concerts at the Felsenreitschule. The Dioscuri, half and twin brothers, one of them mortal, the other immortal, are both in love with the princess Télaïre, who favours Castor. Castor’s death and an offer from their father Jupiter create a conflict of conscience for Pollux…

Reinoud Van Mechelen and Marc Mauillon sing the unequal twins; Jeanine De Bique appears as Télaïre. “Heaven, earth and the waves / Shall glow with a thousand different lights,” says the final chorus: “That is the command of the ruler of the world, / That is the feast of the universe.” The irregular pearl shines on.

Text: Walter Weidringer

First published on 31.05.2025 in Die Presse Kultur Spezial: Salzburger Festspiele

Translation: Alexa Nieschlag