D-S-C-H: Bottled Messages from a Dictatorship

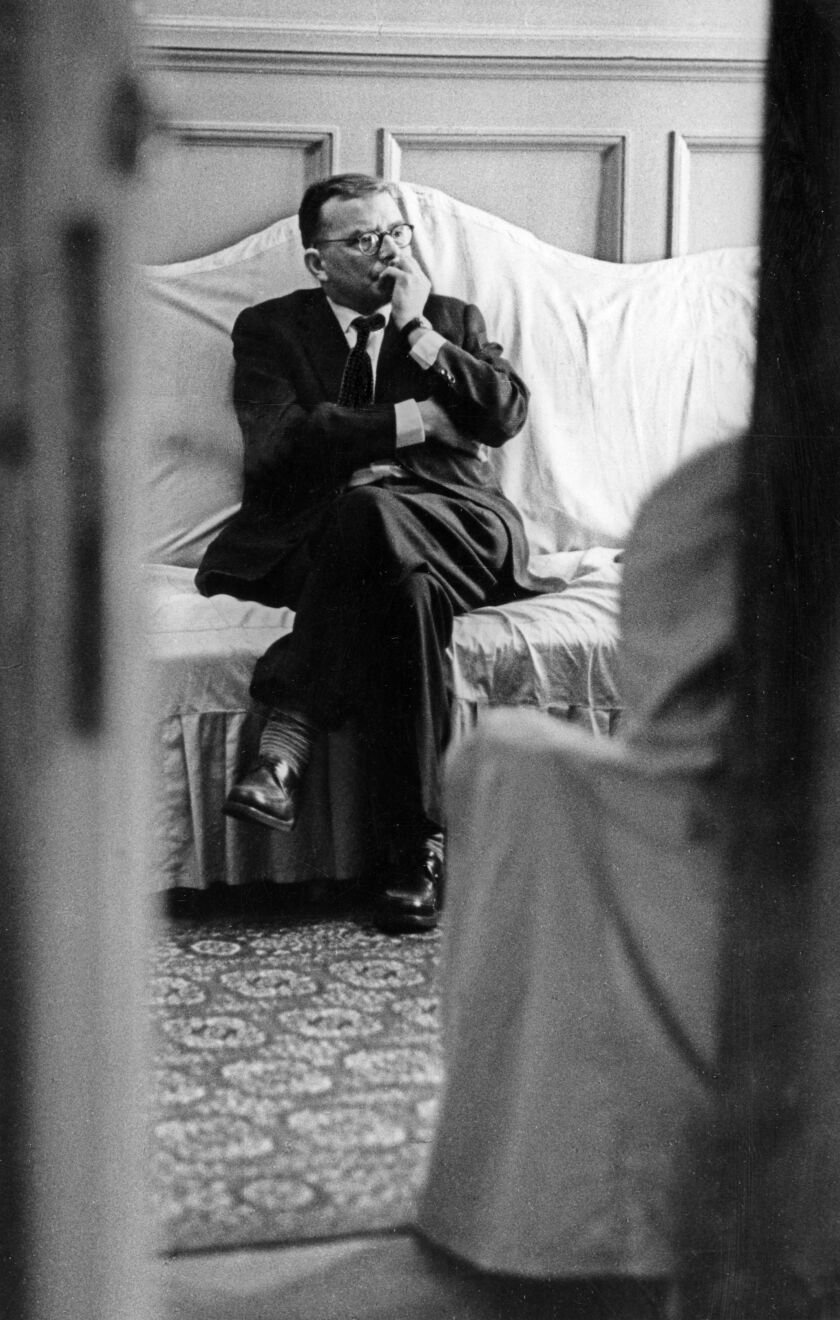

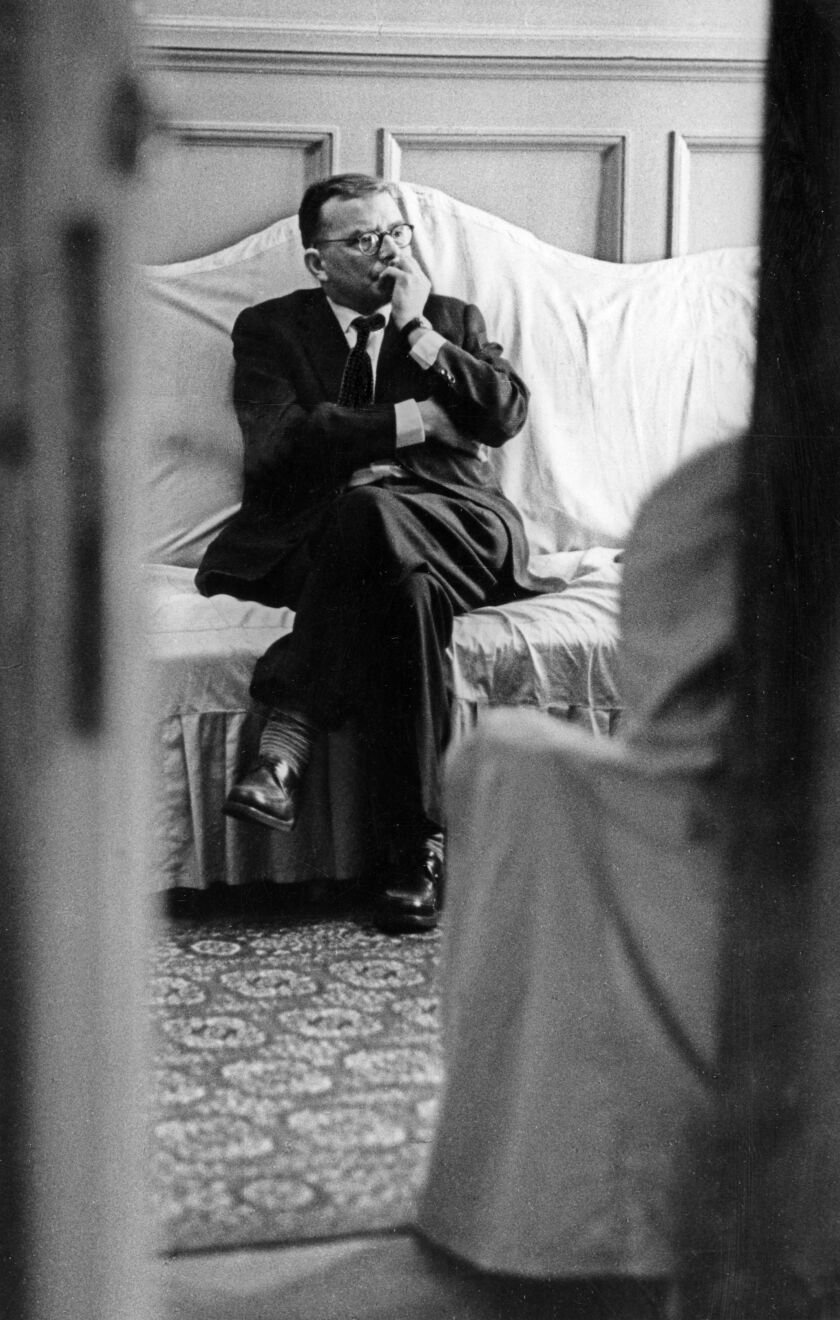

50 years ago, Dmitri Shostakovich died. The Festival dedicates a focus series to this chronicler of art under political pressure.

“During his last years,” writes the author about his main protagonist, the composer, “he increasingly used the marking morendo in his string quartets: ‘dying away’, ‘as if dying’. It was how he marked his own life too. Well, few lives ended fortissimo and in the major. And no one died at the right time. Mussorgsky, Pushkin, Lermontov – they had all died too soon. Tchaikovsky, Rossini, Gogol – they all should have died earlier; perhaps Beethoven as well. It was, of course, not just a problem for famous writers and composers, but for ordinary people too: the problem of living beyond your best span, beyond that point where life can no longer bring joy, instead only disappointment and dreadful happenings. So, he had lived long enough to be dismayed by himself. This was often the way with artists: either they succumbed to vanity, thinking themselves greater than they were, or else to disappointment. Nowadays, he was often inclined to think of himself as a dull, mediocre composer. The self-doubt of the young is nothing compared to the self-doubt of the old. And this, perhaps, was their final triumph over him. Instead of killing him, they had allowed him to live, and by allowing him to live, they had killed him. This was the final, unanswerable irony to his life: that by allowing him to live, they had killed him.” Thus, the writer Julian Barnes describes the aged, deformed, perhaps even broken Dmitri Shostakovich in his biographical novel The Noise of Time (2016). For few artists were life and work so directly dependent upon the exigencies of cultural policy in their homeland as in his case.

Born in St. Petersburg in 1906, still a subject of the Tsar, he began studying music at the age of 13. When he had completed his studies in 1925, his hometown had already been renamed Leningrad and had become, after the revolution, a vibrant centre of international musical life in the Soviet Union, dedicated to the avant-garde. Young Shostakovich quickly enjoyed success in Europe, in North and South America: it was the beginning of a promising career as a composer.

A confused stream of sound. Then, however, Stalin’s terror began. In an article in Pravda published in 1936, Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District was defamed as “deliberate dissonance, a confused stream of sound”. Suddenly, the composer found his artistic and human existence threatened. Contrary to expectations, however, he was spared, even surviving a second reprimand in 1948. The regime used him as an advertisement of Soviet art abroad, while pressurizing him relentlessly at home – even forcing him to join the Communist Party in 1960. Under these dictates, threats and contortions, Shostakovich’s work turned into an eternal attempt at walking a fine line: double meanings and secret messages undermining what “Socialist realism” demanded officially in style and content. To this day, 50 years after his death, his works stand testament how courageous, risk-loving and resistant Shostakovich ultimately remained – and how much his music has to say about us and our present time.

The Salzburg Festival dedicates a programme focus to him, entitled with the four-note cipher he formed from his initials [in German notation] and used in several of his works as an autobiographical and musical signature: the sequence D-S-CH. It is featured prominently in the Symphony No. 10, which the Vienna Philharmonic under Andris Nelsons and also Igor Levit and Lukas Sternath perform, the latter in the arrangement for four-hand piano, in the String Quartet No. 8 (Cuarteto Casals) and the Piano Trio No. 2 (Gidon Kremer, Giedrė Dirvanauskaitė, Evgeny Kissin). Furthermore, the pianist Yulianna Avdeeva and Teodor Currentzis with Utopia, among others, present illuminating cross-references between Shostakovich pieces and works ranging from Johann Sebastian Bach to Gustav Mahler.

Text: Walter Weidringer

Translation: Alexa Nieschlag (except the Julian Barnes passage, quoted from the original)

First published on 31.05.2025 in Die Presse Kultur Spezial: Salzburger Festspiele