‘But not a breath was to be heard when the music began, and the listeners fell very still.’

Sternstunden der Menschheit was Stefan Zweig’s life project: first released with five miniatures in 1927 as a compilation of previously published texts, it instantly became a bestseller. Over the following decades, Zweig added nine more miniatures to the various reprints and translations that appeared. The ‘Sternstunden’ – literally ‘Stellar Moments of Humankind’ – were portrayed as turning points in which the course of human history was decisively changed. They evidently developed into a distinct genre for Zweig, who set about writing them in a focused fashion, even though some of his miniatures – like the one about Magellan – did eventually grow into full-length novels.

Begun during the Roaring Twenties, which Zweig spent on the Kapuzinerberg in Salzburg, the book ended up travelling the world along with its author. The first English translation, published in 1940 with the title The Tide of Fortune, didn’t make it to bookshop shelves: the freshly printed copies ran aground with the bombed ship that was carrying them. ‘I would not have asked to rebuild my life in any other place after the world of my own language sank and was lost to me and my spiritual homeland, Europe, destroyed itself,’ Zweig wrote in a suicide note penned on the other side of the world in 1942. With no strength left for a fresh start in Brazilian exile, he bid farewell to the land of the living.

Whether it is Napoleon meeting his Waterloo, Lenin secretly returning to Russia, Scott getting narrowly beaten to the South Pole, or the laborious laying of the first transatlantic telegraph cable: Zweig’s heroes are always in the wrong place at the right moment – or vice versa. And they all come from the Western Hemisphere. Other regions only appear as objects of conquest, with women similarly glossed over. But what Zweig describes are by no means mere remarkable achievements – with the exceptions of Handel’s Messiah and Goethe’s Marienbad Elegy – but rather milestones mostly born from human error, stubbornness and vanity, with coincidence and chaos taking care of the rest. In addition to the author’s decidedly critical voice, the actions of the men portrayed are always juxtaposed against those of the ‘greatest poet and playwright of all time’ – namely history itself. Drawing another contrast in his foreword, Zweig writes that ‘millions of tedious hours’ must pass before a few crucial seconds make history.

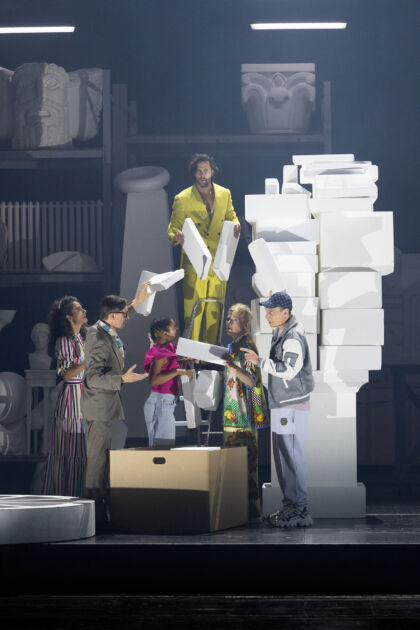

In this musical and theatrical adaptation, Zweig’s evocations of a lost Europe are brought together with South American folk music. It could look something like this: Stefan Zweig is on his deathbed surrounded by a gaggle of obliging ghosts – are they carers or reminders of his past? He lies there, waiting for the poison to take effect. In his head – and in the ears of the audience – the tales from Die Welt von Gestern (The World of Yesterday) are buzzing once again, whispered by various semi-real figures – both actual and imagined visitors. Outside the window, a small brass band plays in a circle around the set and around the theatre, moulding a multi-layered tableau of sounds and images. As if the window had been left open, his final thoughts become mingled with the Brazilian street atmosphere created by the Bavarian-Portuguese itinerant orchestra Munich–Rio–Addio. Zweig’s grandly eloquent depictions of his explorers, poets, thinkers and generals are enveloped by saudade – a specifically Portuguese form of heavy-heartedness that can only be roughly translated as ‘sorrow’, ‘wistfulness’, ‘longing’, ‘homesickness’ or ‘melancholy’.

Following the example of Charles Ives’s vertical style of composition, sounds and fragments of speech become layered one on top of the other like the last few shirts in a steamer trunk. This creates a unique listening experience for every seat in the theatre, in which the individual is connected to the bigger picture and each listener to the greater whole – just as in Zweig’s stories, where personal fates become entangled with the grand workings of the world.

Thom Luz & Katrin Michaels

Translation: Sebastian Smallshaw

Photos and Videos