Hoffmann has seen her again, just a moment ago: Stella, celebrated as a star by everyone; Stella, his lover who has left him. Barely healed wounds break open afresh, and even in the company of his drinking companions Hoffmann is unable to brush aside the feelings aroused in him at seeing her. And then to top it all, Lindorf, that bringer of bad luck, crosses his path… But the crisis unleashes creative energy: as if needing to explain the failure of his love affair to himself and others, Hoffmann improvises three tales in which he splits Stella into three different figures. For, as he announces to his listeners, ‘three souls’ live in common in his (ex-)beloved: ‘Three women in the same woman!’

In 1830s France a veritable cult grew up around E. T. A. Hoffmann, and he remained one of the most popular and influential writers there for the rest of the century. He was admired for the way the ‘fantastique’ – the supernatural – irrupts into reality in his stories and novels, blurring the borders between the interior and the exterior life. But Hoffmann himself was found equally fascinating as a personality, embodying as he did the quintessential inwardly torn Romantic artist; from the outset his early biographers tended to invest his life with legendary qualities. It is thus unsurprising that the works of a number of younger French authors soon not only featured figures inspired by Hoffmann’s texts but also Hoffmann himself: the real-life poet became a literary figure.

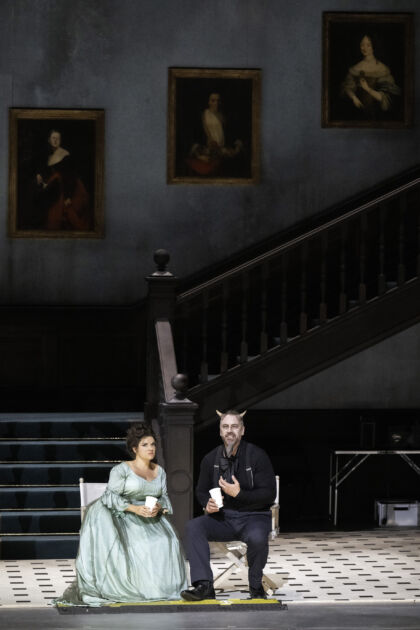

A notable example is Jules Barbier and Michel Carré’s play Les Contes d’Hoffmann from 1851, which Barbier recast as an opera libretto for Jacques Offenbach in 1877. While the three central acts – the ‘tales’ – rework a selection of Hoffmann’s stories, in the ‘real world’ of the two acts that bookend them we encounter Hoffmann as an individual – and as the narrator of the tales. Over and above this, however, in a curious interleaving of levels, Hoffmann appears as the protagonist in his own tales, which are all unhappy love stories. And yet he always stays who he is, and the same could be said for his faithful companion Nicklausse, if it weren’t for the fact that he (or she?) introduces himself at the beginning as ‘the Muse’. Offenbach envisioned a single soprano for the roles of Stella and the figures into which Hoffmann splits her up; Hoffmann’s powerful antagonist Lindorf and his narrative reincarnations – whether bizarre, uncanny or demonic – are likewise conceived as a fourfold role. Thus in Les Contes d’Hoffmann the worlds of reality and fantasy, Hoffmann’s personal situation and his artistic creations are tightly interwoven.

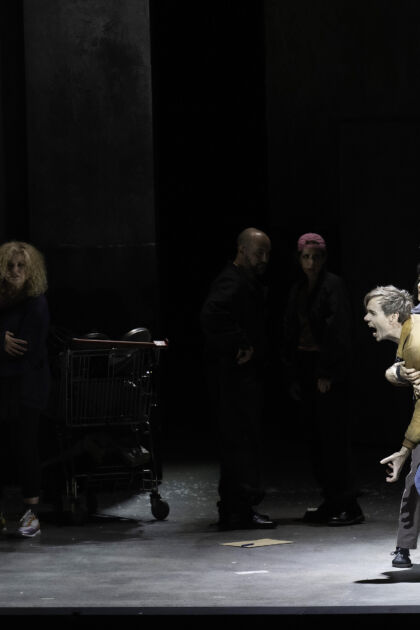

In her staging, the French director Mariame Clément will explore the relationship between art and real life by linking the three ‘tales’ with individual stages of Hoffmann’s biography as an artist. This has decisive consequences for the female figures, or rather for the way we perceive the images that Hoffmann projects onto Stella: the angelic but emotionally cold Olympia, who turns out to be a doll; Antonia, who is not prepared to renounce her artistic vocation and sings herself to death; the courtesan Giulietta, who as a femme fatale merely feigns emotions in order to trick Hoffmann into giving her his soul. For Mariame Clément it is crucial to give these figures independent life, real identities and thus the potential to challenge the images of femininity imposed on them.

In Les Contes d’Hoffmann, composed for the Opéra-Comique in Paris, Offenbach saw his last chance to prove all those who had him marked down as a mere composer of operettas to be wrong. In fact, he had written stage works in almost all genres, and one fascinating aspect of his final ‘opéra fantastique’, which he was not quite able to complete before his death in October 1880, is its very stylistic variety, one might even say heterogeneity. In Salzburg Marc Minkowski will bring the score, veering as it does between trenchant humour, touching sensibility, romantic exuberance and tragic intensity, to scintillating life.

Christian Arseni

Translation: Sophie Kidd