The Scaffold – and Beauty

Donizetti‘s Maria Stuarda reveals the relentless, brutal mechanisms of politics and violence, in the musical guise of bel canto’s formalism and freedom.

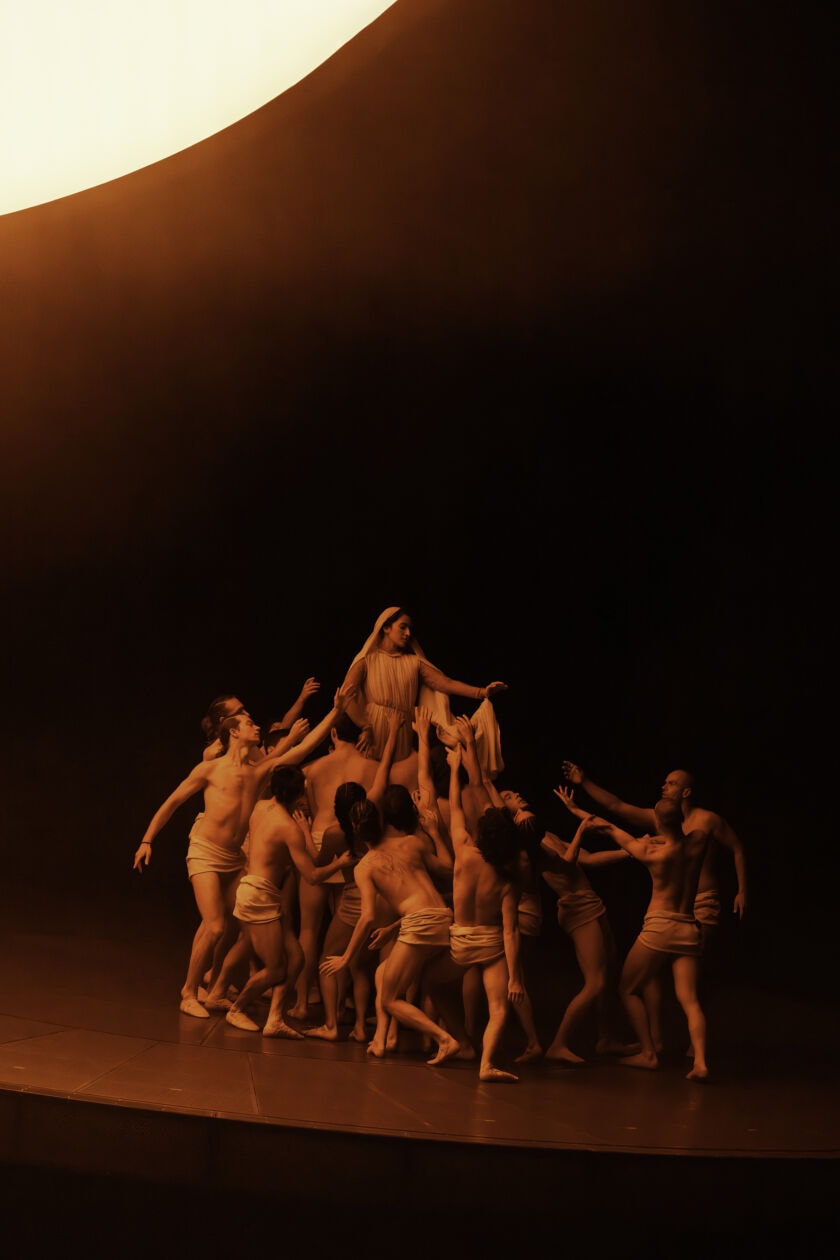

The image she has decided to project is meticulously planned, to the last detail: the unusually tall, pale, refined 44-year-old with the long chestnut hair has carefully chosen her outfit. She is wearing a dark brown velvet dress with a high white ruff, a white veil on her head; also a black coat made of satin and silk with a long train – and red gloves. It is complemented by unmistakable insignia of her Catholic faith: rosaries on the belt, a golden crucifix around her neck.

The fact that underneath all these heavy festive robes, which don’t even allow her to move without the help of others, there is also a red corsage and underdress is not known yet to the grim-faced onlookers as she walks into the great hall at Fotheringhay Castle, attended by those ladies-in-waiting still left to her. By the old Julian calendar – which is still in effect here, because no one wants to implement reforms initiated by a Pope – the date is Wednesday, 8 February 1587 – and Mary Stuart is heading to her own execution. The executioner will need three blows until the head is finally severed from the torso.

Mary, Queen of Scots: to this day, Mary Stuart is known by this title in the English-speaking world. From the beginning, people were fascinated and repelled by her character and her fate, were either her faithful servants or opposed her by any means. Some saw a Catholic beacon of hope in her, the legitimate heir to the English throne, a mother and martyr, while others considered her a Papist machinator and even the murderess of her husband who was also keen to rid herself of her rival in London. The latter was Queen Elizabeth I, the Virgin Queen: Protestant, unmarried, childless.

After all the embittered propaganda and counter-propaganda put out by the opposed yet similar queens and their courts, it would be silly, even wrong to accuse Friedrich Schiller and later Gaetano Donizetti of blithely ignoring historical truth in the tragedy Maria Stuart and the opera Maria Stuarda. In a letter to Goethe written in 1799, Schiller emphasized that his imagination had won “freedom over history”: both the love conflict of Leicester, who stands between the two women, and the only encounter between the queens, ending in uproar, are invented. It’s no wonder, however, that in both Schiller’s case and in Donizetti’s, whose librettist Giuseppe Bardari referred to Schiller’s play via translation, it is this very confrontation that becomes a highlight of the work itself, but moreover of the entire genre in its respective era: on stage, exemplary artistic truth trumps authenticity, pointing as it does beyond the concrete case.

Never mind the difference between fantasy and reality, though: suddenly, things looked like they were going disastrously wrong for Donizetti, after everything had been put in motion for a successful premiere of Maria Stuarda at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples at the end of September 1834. For unknown reasons – either on a whim, or because of a sudden sense of duty – the censor, or possibly even the King of the Two Sicilies himself, Ferdinand II, surprisingly prohibited the opera’s performance.

This despite the fact that the subject had been set to music several times, effortlessly clearing the hurdle of censorship every time: for example by Pietro Casella (Florence, 1812), Pasquale Sogner (Venice, 1814) or Saverio Mercadante (Bologna, 1821). The Catholic Italian states obviously had a marked interest in the Scottish queen.

Anecdote, however, is wiser, giving meaning and logic to coincidence or despotism: if it is to be believed, the Queen of Naples, Maria Christina of Savoy, who was keenly interested in music and at the same time particularly pious (she was beatified by Pope Francis in 2014), attended the dress rehearsal. Given Mary’s musical confession of her sins in Act II, and/or because of the remote relationship between the House of Savoy with the House of Stuart, the Queen had been spontaneously shocked: “In keeping with the conventions of the time,” Leopold Kantner drily remarked, “she documented this with a fainting spell, reason enough to cancel the opera for good the next day, regardless of the enthusiasm the music sparked in the performers.”

Violence, even during rehearsals. Another reason for the ban might have been a scandal during rehearsals, very likely to have been wildly exaggerated, ensuring it would spread like wildfire on the grapevine: the singers Giuseppina Ronzi de Begnis (Maria) and Anna del Serre (Elisabetta), rivals from the start, had locked horns on stage – literally. The title heroine had put so much emphasis on the triumphal, scornful exclamation “vil bastarda” (vile bastard) which the piece put into her mouth that del Serre could only take it personally, given their shared history. A wild brawl ensued. Del Serre was said to have been ill for two weeks after – unfortunately, it is not known how many of those days were required for the black-and-blue marks to recede and how many for even a superficial healing of her injured pride.

What could Donizetti and Bardari do but save their premiere by removing any offending elements from the work? Thus, Maria Stuarda became Buondelmonte within five days of fevered work, a drama of jealousy set during the era of the warring Ghibellines and Guelfs during the medieval Italian Empire, ending with the death of the title hero and one of the two rivals Bianca and Irene. The composer lamented the changes as a “barbaro cambiamento” and “ciabattinismo”, a barbarian change and cobbling-together of the rest: “il maestro Donizetti straccia, poi fà e rifà” – tearing up, writing, and then rewriting.

After another eleven days of rehearsals, Naples saw the – only moderately successful – world premiere of a piece that no one had meant to write in this form. Yet written it had been.

Only a good year later could Maria Stuarda be performed under this title, at La Scala in Milan – this time, the title role had to be rewritten for the vocal powers of the great, though hardly uncomplicated Maria Malibran: Donizetti, caught up in the mechanisms of the opera world of his era. Who, then, would notice the extent to which he had made the large, extensive forms of his colleague Vincenzo Bellini his own, especially in Maria’s cantilenas, most of them expansive affairs? His portrayal of Elisabetta, on the other hand, is more nervous, tense, and agitated.

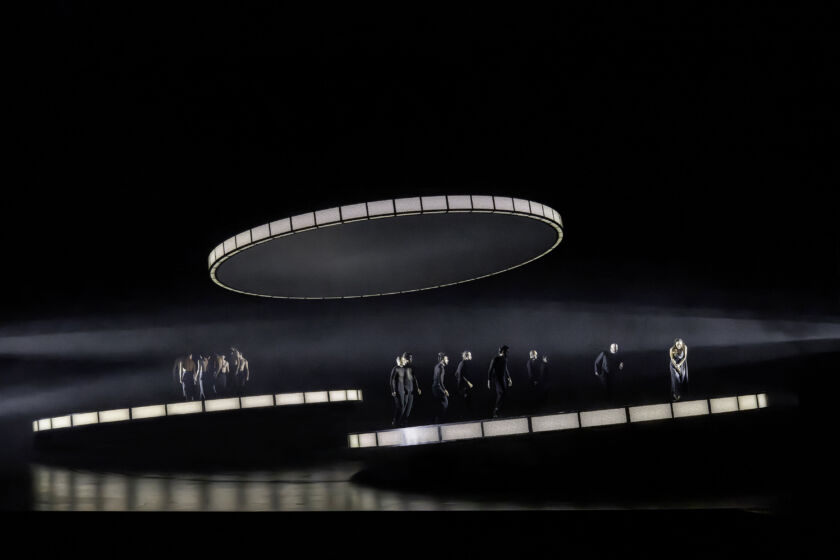

Mankind, machine. Mechanisms: they are – literally – also the specialty of the theatre-maker Ulrich Rasche, born in Bochum in 1969. As a set designer and director, he is known for his revolving stage effects, for continuous movement, for his monumental exploration of machines, the counterpart of all things human. The fact that its mechanical nature is also one of the old, false prejudices against Italian opera of the first half of the 19th century, the so-called bel canto era, can be interpreted as a contrast or a congruence – depending on your point of view.

Two large rotating turntables will dominate Rasche’s stage, one for each queen, and both will be present the entire time. The central issue and question the director thereby poses is: “How much power can an individual exert out of considerations of their own? How far is the individual caught in a construct of power and representation, forcing it to make certain decisions out of necessity?” Far more than the conventional triangular story with Leicester as its hinge and turning point – a role sung here by the award-winning young Uzbek tenor Bekhzod Davronov – Rasche is interested in “the history of the two women, their mutual dependence: Elizabeth cannot do anything without considering Mary – a curious situation, for Mary is the prisoner here. Isn’t Elizabeth a prisoner too, though, in some way?”

“Ulrich’s Nathan der Weise in Salzburg was fantastic,“ the conductor Antonello Manacorda is convinced – he is looking forward to the first joint opera project with his friend of many years. Manacorda, born in Turin in 1970 and at home in Berlin, began his career as a violinist, becoming concertmaster in the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra in 1994 and later working at the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, gathering experience with conductors such as Claudio Abbado, Pierre Boulez and Bernard Haitink. Following initial success on the conductor’s podium, he studied conducting formally with the legendary Finnish teacher Jorma Panula. For 15 years, he served as the chief conductor of the Kammerakademie Potsdam, with which he has made numerous award-winning recordings. In addition, Manacorda is a sought-after guest conductor, both for historically informed ensembles and traditional opera and symphony orchestras. At the Vienna State Opera, for example, he has conducted various performances and led the premiere of Die Entführung aus dem Serail.

A pragmatic approach to the score. Manacorda takes a pragmatic approach: “Every single score you open poses questions of performance practice,” he says. “The point is to understand the language – I would even say: the dialect – of the composer in question, and try to reproduce it. Sometimes old instruments help in this process, sometimes modern ones offer more possibilities.” The most important question is not whether historically informed or modern, but, in this case: “What does Donizetti sound like?”

The basis will be the urtext of the Naples version, expanded by later changes for Maria Malibran, streamlining the dramaturgical knot even further. Thus, the piece opens not with the overture composed later for La Scala, but, as Manacorda enthusiastically notes, with “the incredibly beautiful clarinet recitative, an exemplary model of instrumental bel canto which immediately draws us into the story”. Regarding ancient prejudice, the conductor has clear principles: “One always thinks that in this style, the orchestra serves only the vocalism. And of course, the voices deliver the text and also the greatest expression. But the sound from the pit is essential to the overall effect. I always say that we have to analyse, structure and intone the music as carefully as a good director guides the action on stage.”

This also means applying the rules of bel canto: “With our fabulous rivals, Lisette Oropesa and Kate Lindsey, we will work on vocal ornamentations that match the style.” The most important element, however, is making the sparks fly in the drama of their struggle. In the end, when Maria walks towards the scaffold, Manacorda thinks she is “a mix bewteen a lioness and a saint, also in her music”. Manacorda considers Rasche’s style of directing an example of the principle “panta rhei”: “Everything is in continuous motion – and that, I find, is an incredibly fascinating contrast with traditional bel canto, where the protagonists simply stand and sing. Rasche brings a physicality to this which, in combination with the abstract staging solution, reveals the essence of being.”

Text: Walter Weidringer

Translation: Alexa Nieschlag

First published on 31.05.2025 in Die Presse Kultur Spezial: Salzburger Festspiele