‘Cruel woman, you have signed a sister‘s death warrant!’

Mary Stuart, Queen of Scotland — her name will be linked in perpetuity with another name: Elizabeth I of England. Mary and Elizabeth: two queens, two adversaries, two women in the middle of the 16th century. Although ‘sisters and cousins’, they never actually encountered each other in the flesh — contrary to the fictional conceit.

What ties them together for ever is a terrible fact: one of them must die. Their fatal enmity is ignited by a single question: who does the throne of England belong to? Elizabeth? Yes, indisputably, say the English lawyers for the Crown. And yet in equal measure — no: as a bastard, she is considered unworthy of the throne by the Catholic world; Mary alone has the legitimate claim. In this predicament, both women would probably have preferred — deep down — to preserve a semi- or false peace. But that appears impossible: as Mary infiltrates the ‘Elizabeth system’ like a dangerous virus, the fragile balance begins to be shaken. The constellation of the historic hour does not allow the pair to coexist: Mary is beheaded in 1587.

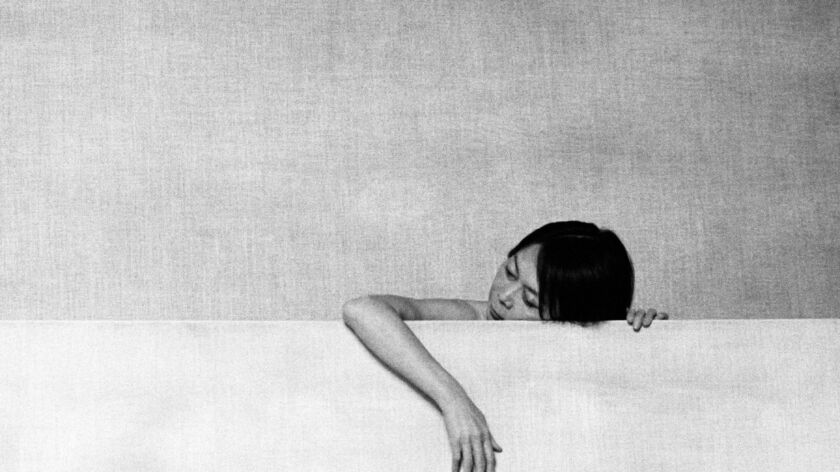

In her more than forty years on the throne, Elizabeth I impressed her name on the epoch, making it the ‘Elizabethan’ age. All her life she successfully resisted sharing her power with a husband, which earned her the epithet of the Virgin Queen. Mary Stuart passes almost ghostlike through the history of power, and she would arguably be all but forgotten had she not suffered her singular fate. Leaving no notable historical or cultural legacy, she has nonetheless exercised an unparalleled attraction on posterity. Her rise to power was meteoric: Queen of Scotland at the age of just six days, betrothed at six, by 17 Queen of France. Everything seems to come to her as if in a dream. Her men, her marriages, her child. And just as quickly it all fades, withers and is gone, and she awakes disappointed and distraught. In this confusing state, seeking aid, she arrives in England, where another woman has already held the throne for ten years.

Mary and Elizabeth embody, as Stefan Zweig puts it, a ‘great world-historical antithesis […] worked out contrapuntally down to the last detail’. In his tragedy of 1800, Friedrich Schiller decisively shaped how these two women were seen in later ages, telling a story of political intrigue on the one hand and the gaining of freedom and autonomy on the other.

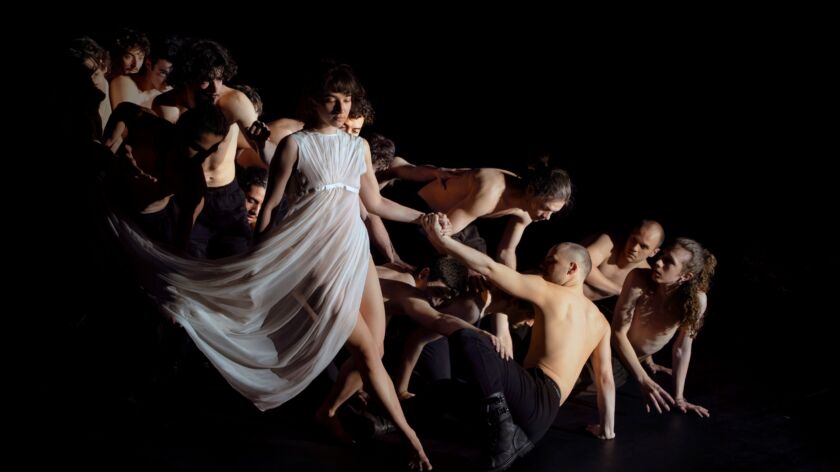

None of this complexity is to be found in Donizetti’s opera from 1835. Here the focus is on the emotional lives of the two women, compressed into the final 24 hours before the death warrant is signed and Mary goes to her execution. In this brief period of time they experience all conceivable emotional extremes: the joy of victory, the collapse into depression, torturous self-questioning, the alluring anticipation of liberation and the paralysing fear of death.

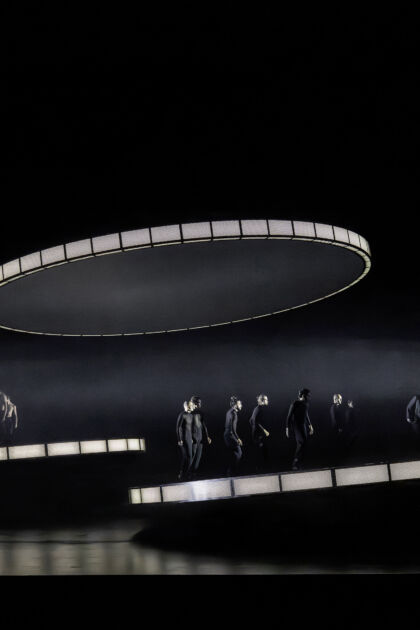

Both Elizabeth and Mary are observed, judged, manipulated and controlled to equal degrees. As representatives of state power, they possess the ‘two bodies’ of a monarch: the ‘body natural’, mortal and imperfect, and the ‘body politic’, which is perfect and never dies. This body is the harshly illuminated, rigid carapace of the vast apparatus of power to which both women are bound — hard enough to drive out tender imaginings for good, and to destroy any illusion of happiness. And thus, Mary and Elizabeth — each imprisoned in their own loneliness — are the same. They circle around each other, almost perfectly balanced, as in a dance. The longer they dance, the closer the two queens approach each other, perhaps becoming for a brief moment beyond the constraints of power what they actually are: fragile creatures seeking a foothold in the world.

Yvonne Gebauer

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Production Images