The Opera Programme 2024

“Compassion is the only law of mankind,” – this phrase from Dostoyevsky’s novel The Idiot becomes the pivotal point of Weinberg’s opera.

Two world wars, millions of people murdered on the battlefields and in the concentration camps. The world seemed one big Cold War of ideologies. Taking this as a backdrop, in L’homme revolté (published in English as The Rebel), Albert Camus sketched his idea of an ideal revolt, a revolt of solidarity in the name of humanity: “I am in revolt, therefore we are”.

The protagonists of the operas of this upcoming Festival summer all bear the notion of revolt within them. They believe in a different set of rules, adhering to other principles than the societies in which they are mere outsiders. Dostoyevsky’s “Gambler” in the eponymous opera by Sergey Prokofiev is such a character, obsessive and exposed, on the fringes of society. He is one of Dostoyevsky’s typical heroes, or antiheroes, searching so urgently for the meaning of life, the meaning of existence, that their solutions can only be extreme. The rotational movement in roulette becomes a falling motion, pinpointing the decisive element: failure. The metaphor of the gambler who draws everything around him into a maelstrom of destruction and doom becomes a symbol, a metaphor of our world today.

The character of the “Idiot”, as in the original meaning of the word, indicates someone who does not belong to the polis, but stands outside society, someone who rejects this society – in our case, a corrupt one. “Compassion is the only law of mankind,” – this phrase from Dostoyevsky’s novel The Idiot becomes the pivotal point of Weinberg’s opera. In the character of Prince Myshkin, it paints no more and no less than the utopia of a “truly perfect and beautiful human being”, a human full of empathy and sympathy. Character traits he shares with the ruler in Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito – this wonderwork will also be performed in Salzburg this summer.

And finally, Don Giovanni and Hoffmann. Like a will-o’-the-wisp, one of them, Giovanni, wanders this empty world like a lost alien, driven by excess; his morality does not correspond to the norm, it is focused only towards intensity. Hoffmann, on the other hand, is infinitely more passive: a romantic in love, an enthusiastic traveller, caught in a kind of delirium, a projection, his innermost torn to pieces.

These emotional boiling points, the elementary beauty of excess, the ecstasy of existence – all this we will trace this summer, in the spirit of Stefan Zweig, who wrote that without those who “overstep the boundaries”, humanity would know less about “the mysteries of existence”.

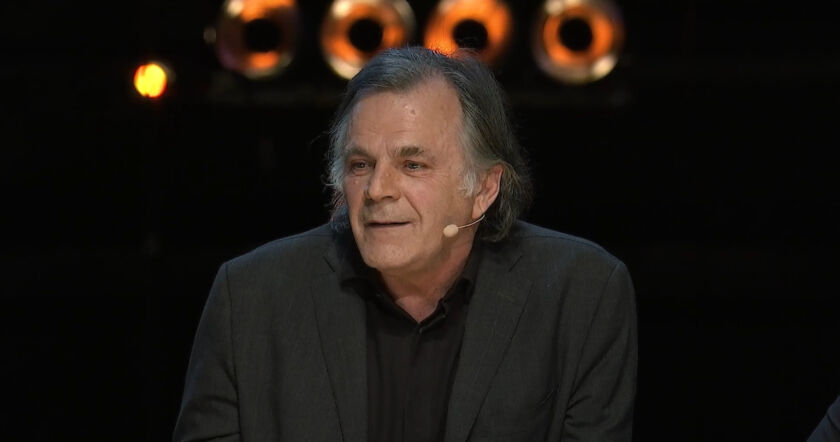

Markus Hinterhäuser • Artistic Director

Translation: Alexa Nieschlag

First published in the Festival insert of Salzburger Nachrichten 2024